PBRS AND PVRS…

If a plant has Plant Breeder Rights, you will often see the acronym ‘PBR’ after the plant name. Or a funny looking ‘b’ symbol (see below). They are also known as ‘Plant Variety Rights’ or PVRs. PBRs are basically registered and patented varieties (see the technical differences here) which prohibit propagation for re-selling without a license. As part of the application, they must provide evidence that the plants are new, distinct, uniform and stable. To give you an idea of the scale; in the UK, in 2016, 3,074 applications were made to the Cambridge-based Plant Variety Rights Office (PVRO).

In the UK, legislation for PBRs falls under the Plant Varieties Act 1997. The work of the PVRO falls under the larger International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV). Whilst each country has some flexibility over how exactly they legislate for PBR protection, the UPOV ensures that it’s easier for signatory countries to follow a global code of conduct.

WHY DO WE NEED PLANT BREEDER RIGHTS?

PBRs are in place to recognise that many breeders invest substantial time and money into developing new plant strains. As such plant breeder rights allow the breeder to trace and take royalties from any plants that are sold. For every successful new plant variety there will be numerous that don’t make the cut. Royalties from PBR sales allow recouping of such hidden costs, plus some extra for their next program. I imagine there’s probably some in it for the shareholders too…

But not all PBRs come to the market with such an extensive research program, like finding one by chance. You can start to see this is where some people start to have issues with the designation. Consider for example, the opinions given in this article from the Hardy Plant Society. I agree that the ‘owning’ of genetic material can feel a little ‘god-like’. But that ‘chance seedling’ still needs years of development ,until a steady source of stable genetic material can be developed. This involves a ton of paperwork, tracing and testing, before it can be rolled out in huge numbers, often globally.

The RHS has a useful presentation to help you if you’re a budding plant breeder or you come across that ‘chance seedling’.

The wider implications of Plant Breeder Rights

PBRs are not particularly new. Europe issued the first PBRs in the 1940’s. Patenting of plant material was around in the US around ten years before that. There’s an interesting review on the impact of PBRs in developing countries. In Latin American countries, at least, the impact has been viewed as positive. This is due to the ‘farmers’ rights allowance’ (see below for more). Less wealthy farmers can save seed from PBR varieties, increasing year-to-year profit margins. All the while concurrently stimulating breeding from a declining industry. This is particularly for important crops like soya. There is also an exception that the varieties can be used for research and subsequent breeding. The latter requires permission from the original license holder.

Done correctly the momentum behind PBRs can result in some excellent and novel plant varieties (and likely some bad ones). Certainly a plant generally has to be pretty special for a breeder to go through the hassle of registering and paying for a PBR. This includes ensuring that you have the legal capacity to pursue any breach of the rights.

ARE PBRS (AND PVRS) EFFECTIVE?

The threat of legal action doesn’t deter everyone though and you will find examples of these plants for sale through unofficial channels. Whether this is knowingly from clearly labelled purchases, or unwittingly from a long line of ‘plant Chinese whispers’… where the message has become lost along the way. Often people are genuinely not aware, or ignorant, that they exist and should be checked.

Part of the problem is the lack of a comprehensive list. This is the best I could find for the UK but I don’t think it has everything. Brexit is currently partly responsible at this stage. In many countries you can propagate for personal use through an allowance in the legislation called ‘farmers’ rights’, however this does not extend fully to the UK. Where National Collection holders fall under that, it’s a bit more vague. Since they are in the interests of the nation and there is no commercial gain from propagating a few plants each year, I don’t see there being a problem. Plus, directed by experts in their given field, PBRs can actually help fund National Collections.

PROBLEMS WITH PBRS AND PVRS

Whatever your opinion on the story so far, these varieties do tend to be more expensive for the typical nursery and individual to acquire. The economics of ‘tightened’ availability tends to drive up prices. A certain price has to be reached in order to ensure enough profit atop the royalties cut. Smaller nurseries particularly feel the pinch here, because they often rely on self-propagating of plants from specimens already held in stock.

Because of their limitations on propagation and links with commerciality, it’s my opinion that plants with PBRs are at a higher risk of becoming lost. Or at least it’s much more polarised. It’s the bad ones that don’t maintain popularity which are at a much greater risk. Since it’s 20-30 years before a PBR expires, once the initial rush for the variety has died down, that’s plenty of time for a plant to be pushed to the back of the shelf and superseded by the next great new breeding breakthrough. Classic and popular varieties do tend to stand the test of time. Those that have had the effort and resources put into a patent may be more likely to stand the test of time.

ARMERIA PBR VARIETIES

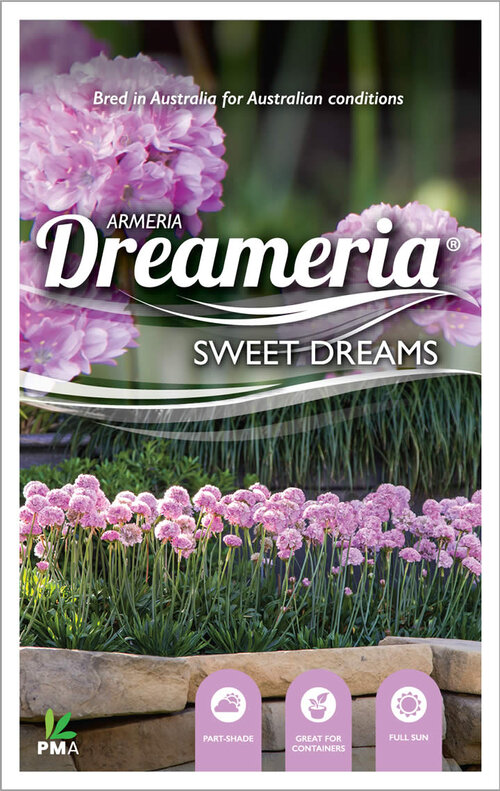

The only Armeria with PBRs that I’ve come across so far are the Dreameria ® Series. This series is made up of six different-coloured x pseudarmeria hybrids, plus A. maritima ‘Pretty Petite’ PBR. These are both held under license by Plants Management Australia. They are basically a consultancy for many ‘breeders and finders of unique garden and landscape plants’. It took ten years to develop the Dreameria® Series. You would probably appreciate that, that’s a significant investment of resources they’ve put in to those plants.

One thing’s for certain though is I’m quite excited about getting the PBR varieties into my collection. So far A. x pseudarmeria (Dreameria ® Series) ‘Sweet Dreams’ PBR is the only one I have. But in five minutes I will hopefully extend this to another two: ‘Daydream’ and ‘Dreamland’. As yet I haven’t found any of the other four PBR varieties in the UK, so the hunt is on!

Coffee I’m drinking: Horsham Coffee Roaster: Peru, Gregorio Esquen, Lot 1

Books I’m currently reading: The Kindness Method by Shahroo Izadi and Killing State by Judith O’Reilly

Previous post: Five Things I Wish I’d Known as a New PhD Student